Will the rapid rise in interest rates push the economy into recession this year? Though not certain, it seems increasingly likely. Following an increase of 2.1% in 2022, growth is slowing this year. In March, the Federal Reserve (Fed) revised their estimates for GDP growth to 0.4% for 2023, and 1.2% for 2024. These figures are close to stalling speed.

The Fed has a dual mandate – foster price stability and full employment. The employment picture remains very strong. In fact, the current low unemployment rate complicates the Fed’s challenge, as wage growth supports consumer spending. The unemployment rate in February was 3.6%, and employment rose by an average of 351,000 jobs per month over the last three months. There remains a large imbalance between job openings and workers who are qualified and available to fill them. With the labor market so tight, the greater threat to growth is inflation. The Fed spent much of 2021 “behind the curve,” delaying interest rate hikes in the hopes inflation proved transitory. It did not. Late to the game, they hiked rates rapidly one year ago and have kept up the pressure with another quarter point increase this past March. The cumulative interest rate increases over the past year have brought the short-term Federal

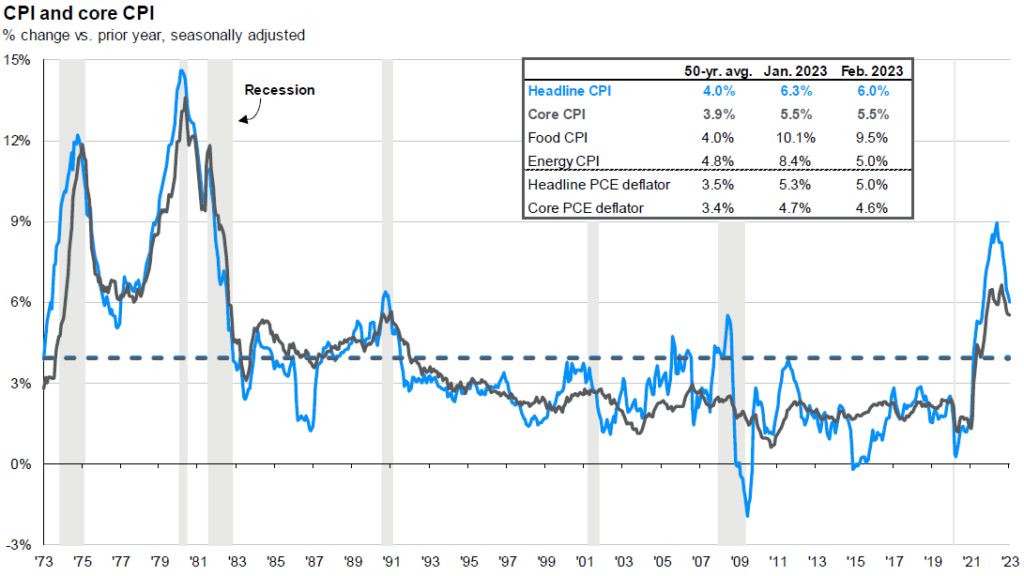

Funds rate to 5%, the highest level since 2007. The Fed acknowledges that inflation remains too high, and they are determined to keep rates elevated until it moderates. With growth already slowing however, the Fed is facing a significant chance of a recession as the necessary trade off to bring inflation under control. While inflation is decreasing, improvements have been slow. Headline CPI inflation was 6.0% in February, while Core CPI inflation (excluding food and energy) was 5.5%. Food inflation was particularly high, at 9.5%, as seen below.

Another consequence of inflation is the uncertainty it creates. Businesses are finding it very difficult to plan for future cost increases or to assess their ability to pass higher costs on to consumers, while lenders fear increases in loan defaults and demand higher compensation in the form of higher interest rates on new loans.

Adding to the challenge, the recent failure of two banks has led to tighter credit conditions. These bank crises were driven more by liquidity concerns than credit issues. They failed because depositors rushed to withdraw money, and the banks could not meet this demand. To date, we have not seen widespread credit losses in the financial system due to borrowers being unable to make loan payments. In this regard, the current stress in the financial system is quite different from that of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. In 2007, the turmoil was driven by risky loans that resulted in defaults when borrowers couldn’t repay them. Today, our strong labor market and healthier financial system make us doubtful that we will experience a severe or lengthy contraction similar to the one in 2008-2009. Nonetheless, even a mild recession would be painful, especially for those who rely more on income than savings and investments to make ends meet. What seems clear is that we are in a period of heightened uncertainty regarding inflation, interest rates, and growth. A so-called “soft landing” is still possible if inflation slows fast enough for the Fed to pause, and perhaps even cut rates as some predict. It’s a tough balancing act, and the Fed is walking a tightrope, trying to achieve a more stable equilibrium.